The Audio Research LS-3 Preamplifier (shown above) not only lacks tone controls of any kind, but it also incorporates a “direct” switch that bypasses the balance and selector switches as well, leaving only the volume control active. Audio Research has been in the high end audio game since 1970 and has been at the very top of the amplification food chain for nearly 45 years. They go to great lengths to fully preserve the integrity of analog signal paths, even in the necessary RIAA phono stage (see I may be a purist, but…). As far as I know, they haven’t provided tone controls on their preamplifiers since the SP-3, released in 1972. Why?.. Tone controls are, by definition, a degradation of an analog audio signal path.

In fact, any circuitry that is “incidental” to the task of amplification is a degradation of the signal path, and very little is essential. This doesn’t mean that what’s there isn’t important, but what’s not there is just as important. A volume control is necessary, as is a selector switch of some kind, phono stage circuitry for vinyl, and in most cases a balance control – both of my listening rooms require an increase of about 2 or 3 decibels in the right channel for proper sound staging, and source components are rarely perfectly balanced between left and right channels.

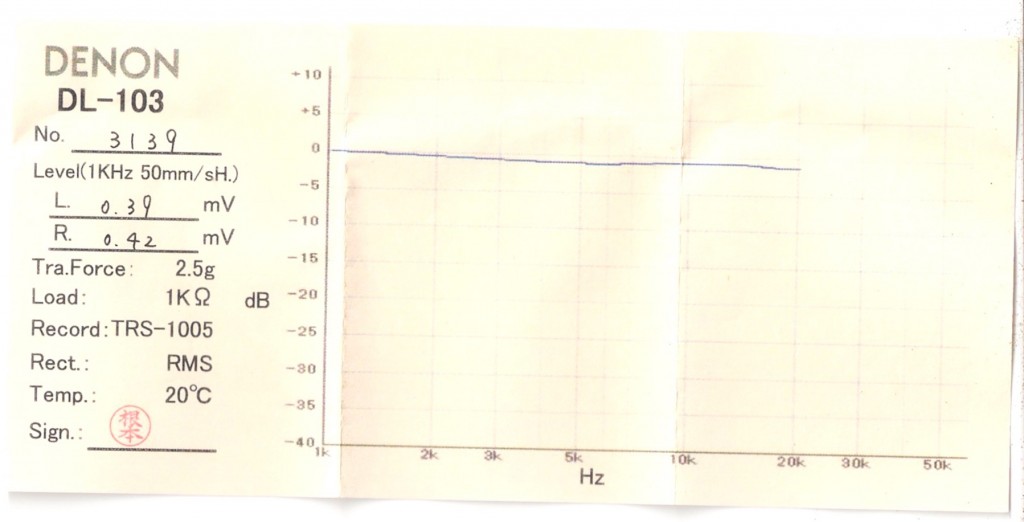

My Denon 103 phono cartridge (The formidable Denon 103 vs. 103R low output moving coil phono cartridges – is there really a difference?…) shipped with the left and right output voltages individually measured, and I discovered the lucky coincidence (even before I checked the hand-measured specifications) that the right channel output is just enough higher than the left to perfectly balance out my room acoustics (right channel output = 0.42 mV, left channel output = 0.39 mV). But that was just that, a lucky coincidence and it could have easily gone the opposite way, making a balance control absolutely essential (or swapping out the left and right channels and thereby reversing the sound stage).

Nearly all Japanese providers of high end audio components in the late 1970s and early 1980s took an opposite approach – the more tone controls and signal manipulations the better since you could use them to create a “flat” frequency response at your listening position in the room. Of course very few listeners used these controls to this end, but rather boosted bass and treble to compensate for inadequacies in either their sources, amplification components, or loudspeakers. Most Japanese components of that era even had a “loudness” control that performed the boosts (corresponding degradation of the signal path) at the flip of a switch. One look at this Sansui integrated amplifier made from 1970 to 1973 tells the story (Doing a little research on vintage Sansui for a customer…).

And who else remembers the elaborate “graphic equalizers” that became popular shortly thereafter?… Lots of lights and sliding controls to insure “proper” degradation of your signal path.

And, perhaps even more offensive to audiophiles, the original DBX 3BX signal processing unit that propurted to somehow, magically, create a delay in your 2 channel system (no 5.1 surround sound here) that simulates the acoustics of a concert hall… seriously?!

I was never a fan, and opted out but was definitely in the minority at the time. Don’t get me wrong, some of these units have a place in pro-audio for live performances in venues with acoustics that vary drastically from location to location, but that’s not how these units were being marketed when first released in the early 1980s (the DBX 3BX came out in 1982). They were “engineered” and sold to the home audio consumer market, and even some high end audiophile retailers began to adopt them.

Not to mention trashing your analog signal path, I also view the corresponding lights very distracting to the listening experience. I even go so far as to apply black tape over any unnecessary lights on my components (which is all of them – even clipping lights on power amplifiers assuming one can hear when their amp is clipping). Some manufactures recognize this and allow the option to extingish such lights (thank you Marantz DSD DAC), and some would rather make sure their logo or other bright (and sometimes even flashing) lights are prominent. Not to bash anyone here, but anyone who’s owned Emotiva gear is fully aware of the “Emotiva Blues” – their crazy bright blue lights, some incorporating their logo and not all of which can be extinguished. Ok, so I’m bashing. I could bash Emotiva all day on many counts, but I suppose they are filling a modern-day niche in the mid-fi market.

Difficult room acoustics can be handled in many other ways, certainly without modification of the analog signal path and most of the time without even resorting to expensive room treatment accessories (see How to upgrade your existing system without spending a nickel and A free upgrade for your planar speakers). I admit I’m a purist and listening to music is a personal endeavor and as such some may prefer drastic alterations to their signal path and accompanying flashing lights. If that’s the case I would respectfully suggest, however, not over-spending on source components, amplifiers, or loudspeakers since the extra cash for very high end audiophile gear is spent to fastidiously accomplish exactly the opposite.