Who else remembers the original Discwasher setup? A great brush with a wood handle that contained a small bottle of the record cleaning solution inside it.

I can’t tell you how many vinyl aficionados who, when speaking of their original record collection have proudly stated, “I took great care of my vinyl, I always cleaned it with the wood brush with the little red bottle inside”. While this is better than no cleaning at all, it pales in comparison to using a proper record cleaning machine. Why? One word: vacuum.

Without a vacuum record cleaning machine all you’re really doing is pushing the dirt around in the grooves and hoping some of it sticks on the brush. While the original Discwasher brush was particularly good at extracting and retaining what dirt and grime it was able to find in your grooves (beware of imitations that came later, the material of the brush itself pales by comparison to the original Discwasher), it still begs the question of it’s fans, “How often did you clean the brush itself?” Unless the answer is “Every time” it’s a fail and what was mostly happening was the sharing of the dirt and grime with other records in your collection. And properly cleaning the brush was no easy task, even with the brush supplied to clean the brush. Which of course leads to the question, “How often did you clean the brush that cleans the brush?” Point is, the dirt and grime never really gets removed without fastidiously cleaning brushes every time a record is cleaned. And even then, the brush itself isn’t extracting the dirt and grime from the record grooves by vacuuming them, but rather by using the stiff bristles of the brush itself and friction and is therefore less efficient and harsher on the vinyl record itself.

I must confess that in my early days of high end audio I was guilty of using a Discwasher, much to the ultimate demise of much of my record collection. I was a teenager and the thought of spending nearly as much for a record cleaning machine as for my turntable instead of, well… buying more records, was a difficult one to get my head around. But without proper vacuum cleaning right from the start, even before the first time playing a record (yes, records ship with residue, dirt, and grime straight from the factory, usually left over from the pressing process itself), the irreparable damage has already begun. Fact is, once the needle hits that tiny spec of dust, dirt, or grime in the groove for the first time, it tends to implant it there, making it that much more difficult to remove the next time the record is cleaned.

So the only way to go for an analogue audiophile, or even just avid record collector, is a vacuum record cleaning machine such as the one show in my Canada system below.

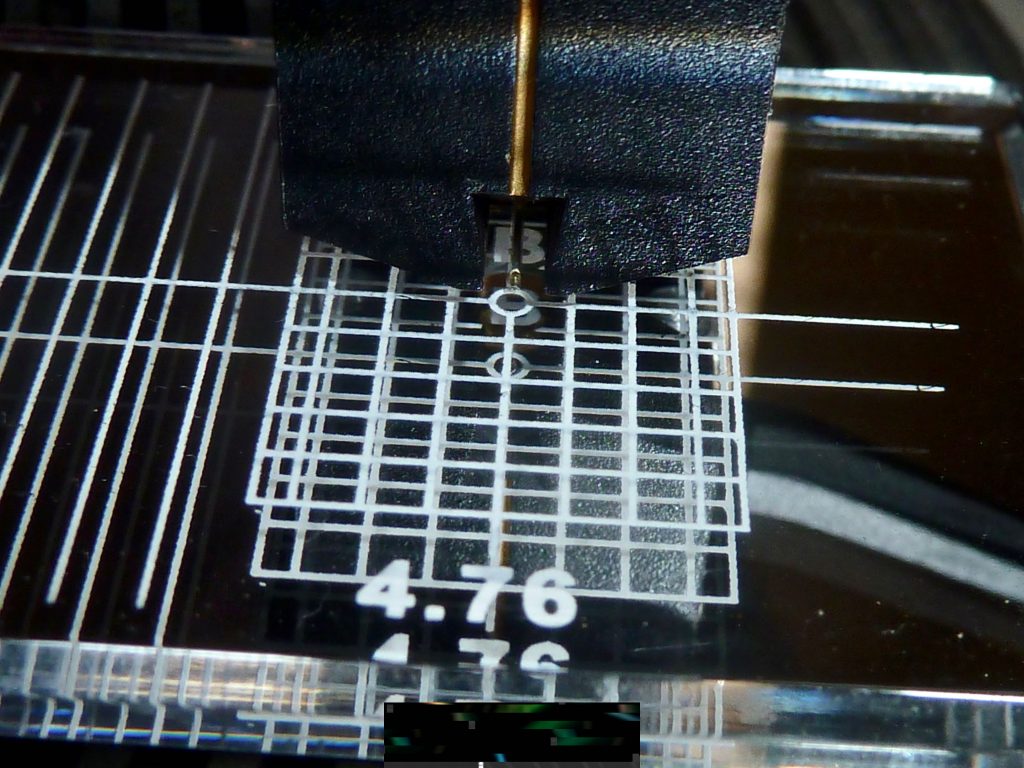

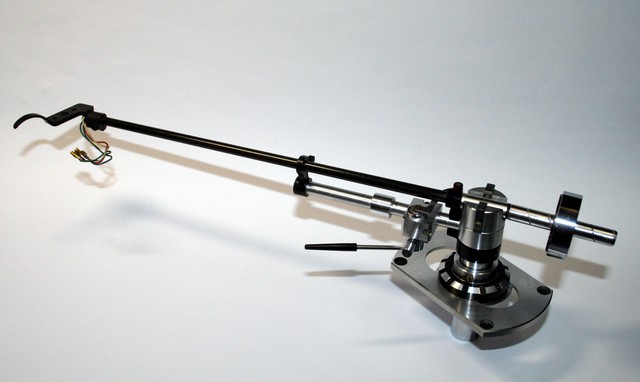

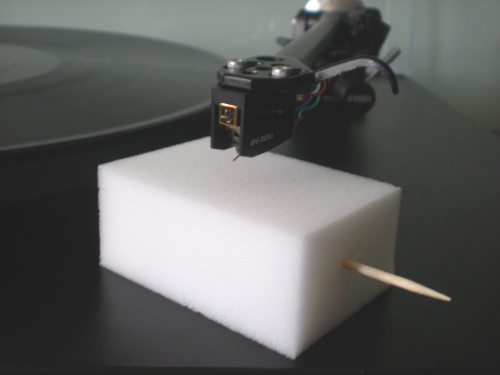

It’s not a complicated machine, just a platter, vacuum tube, and a couple of switches; but they still aren’t cheap with retail prices starting at $500 and rapidly going up from there. The VPI 16.5 shown above is still sold, unchanged and retails for $899. The key to satisfactory results is a high torque motor so you can press fairly hard with the brushes and a high powered vacuum system to remove all that dirt and grime you’re breaking free. I experimented with cheaper ($250 USD), hand-driven record cleaning machine on Maui, the Record Doctor V shown in the photo below, but found it cumbersome to use and difficult to get good results with. This was mostly due to the inconsistent speed due to manual operation combined with the fact that I only had one hand free to apply fluid and brushes to the surface of my vinyl. And, it was such a PITA to use that I found myself not cleaning my records with it before every play, which is step one to record care.

I later replaced it with a great little machine for the money (retails for $500), the Okki Nokki Model RMC. It has a high torque motor, strong vacuum, and reversible operation which I’ve never viewed and essential but hey, it can’t hurt to stroke your vinyl in both directions.

You can spend a great deal more money on record cleaning machines, but all they offer for your extra hard-earned cash is more automation such as wands that apply fluid for you, fixed brushes that spread fluid and others that clean, extra vacuum tubes and fixed brushes on the bottom side so you don’t have to flip the record, and quieter motors (all the machines above are very noisy). All of these niceties are nonessential if you know how to properly clean a record with one of the machines above. So… how is that accomplished? More on that in the next blog.