So I’ve owned and cherished this vintage turntable for over a year now. It’s circa 1978 and I purchased it in absolute mint condition from a very friendly and interested budding audiophile in Calgary. I drove there in -20 degree weather to go pick it up.

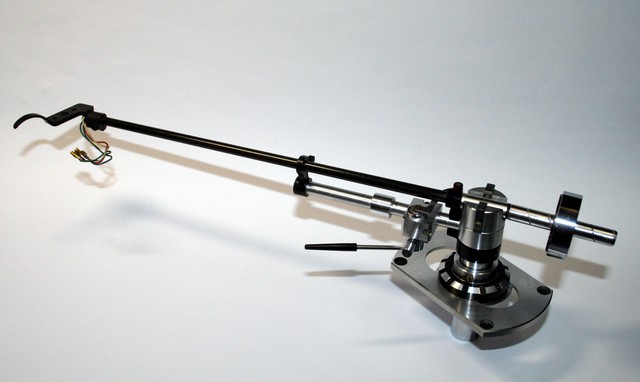

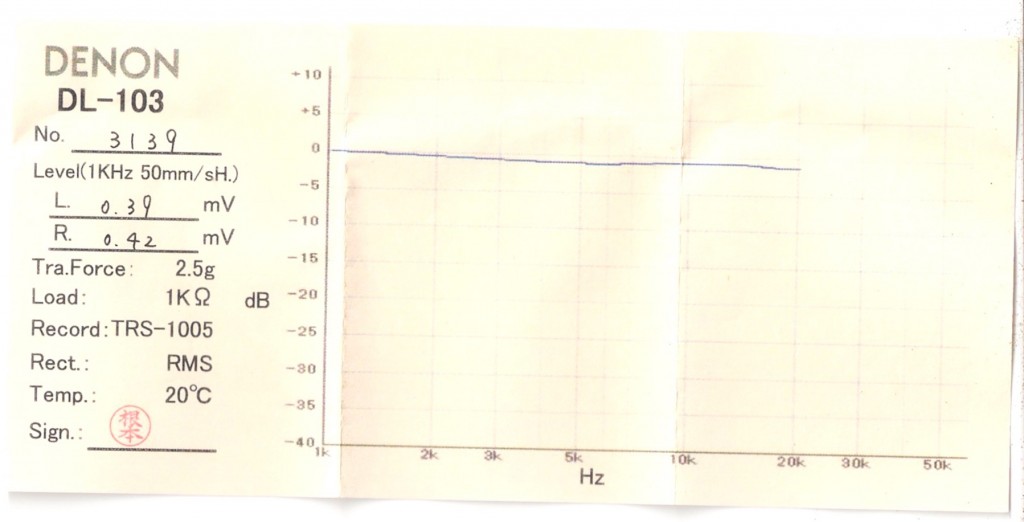

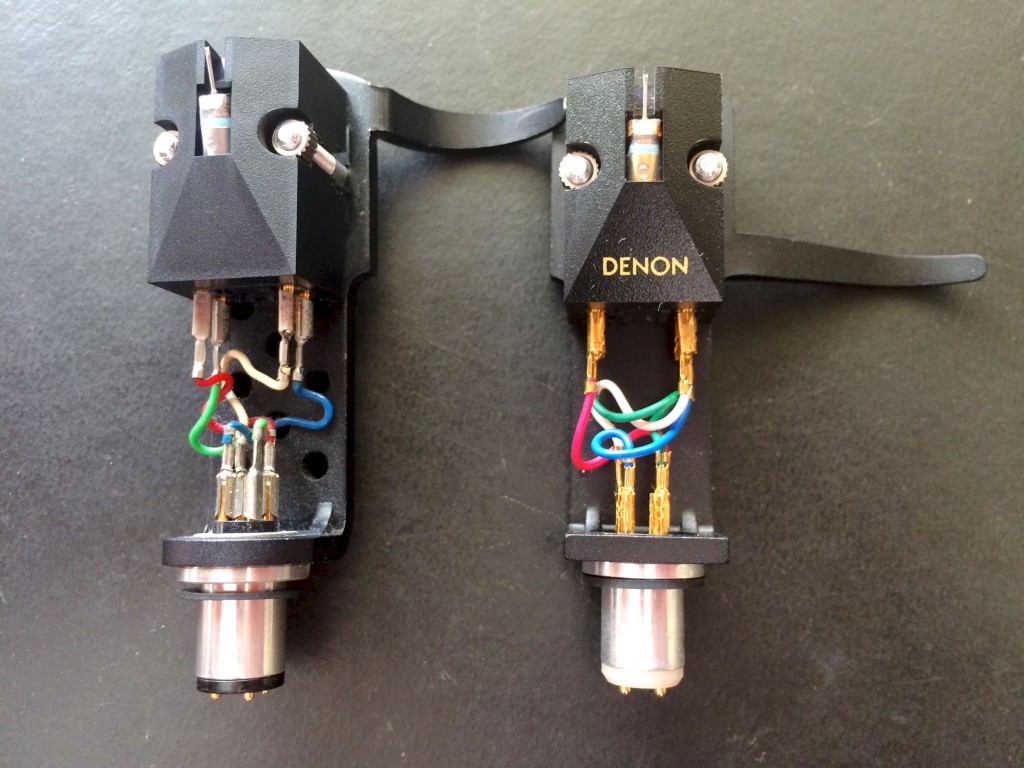

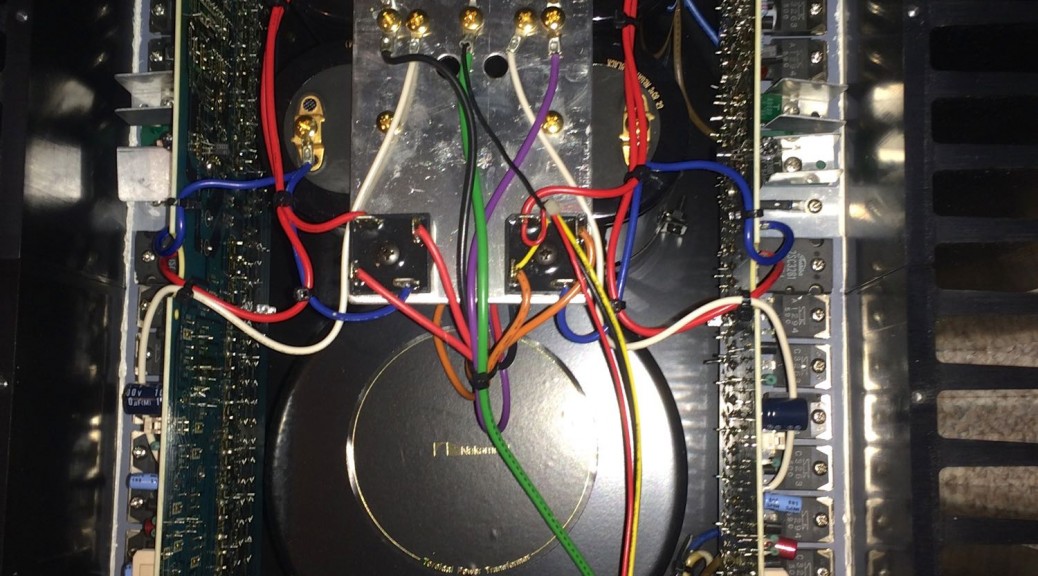

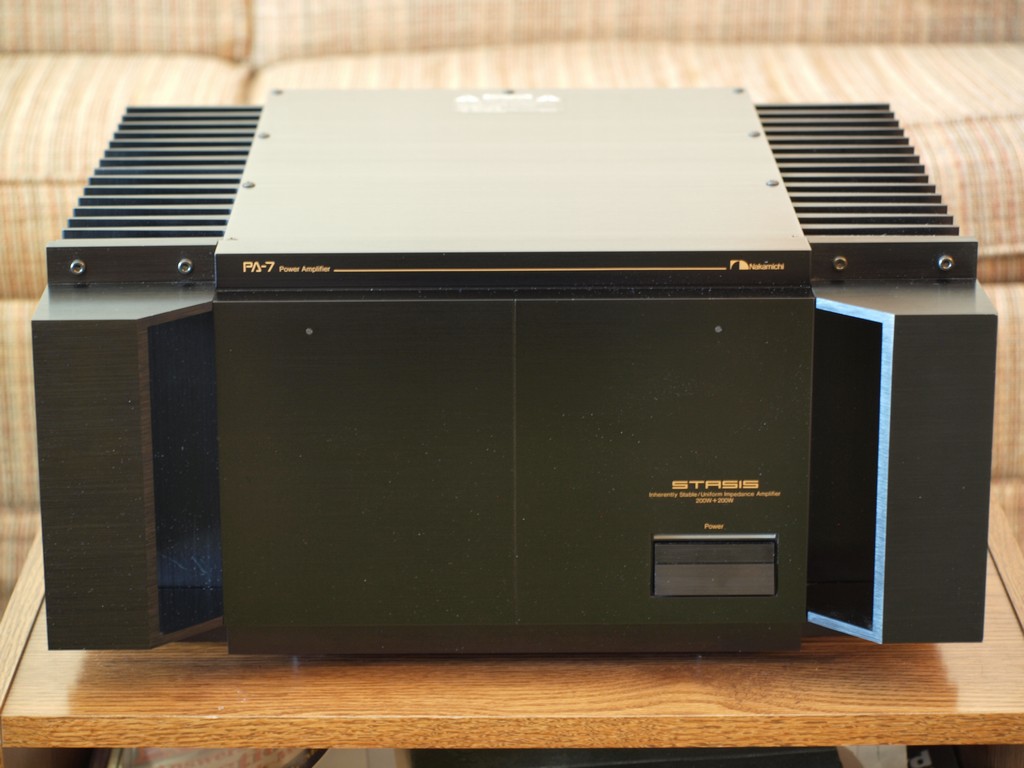

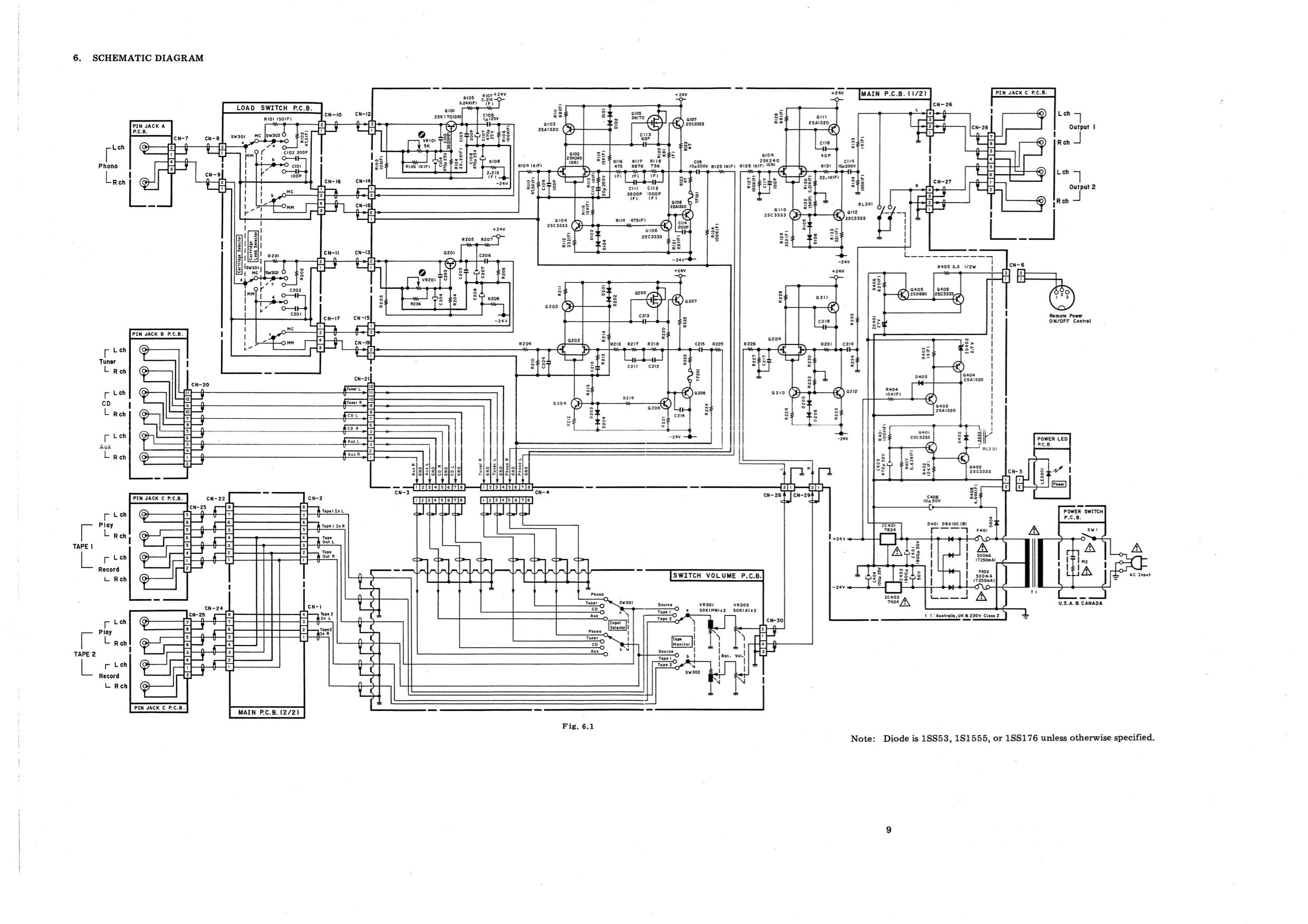

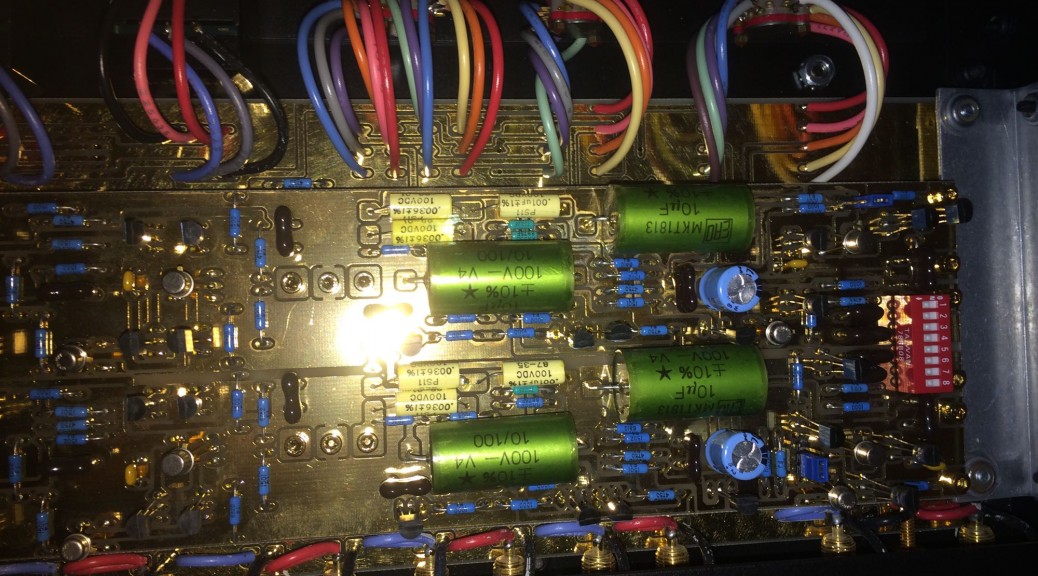

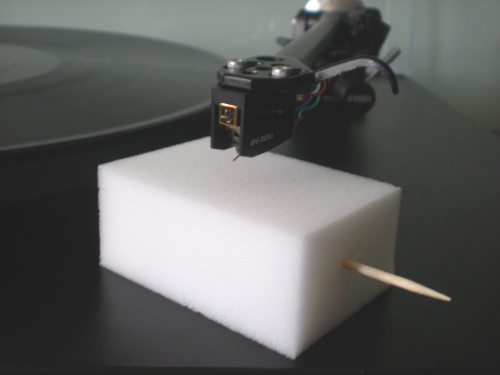

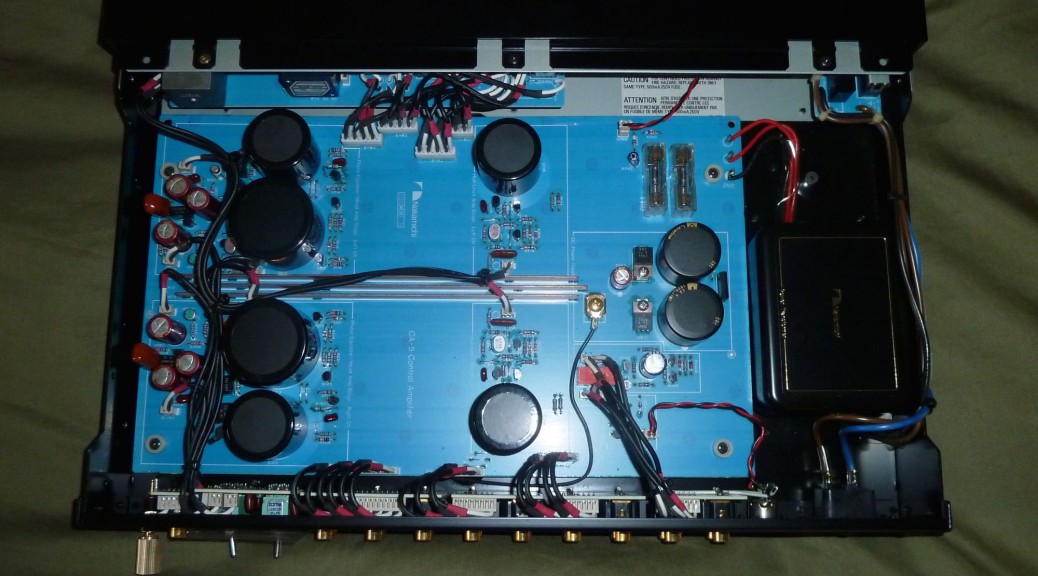

I’ve upgraded the phono cartridge with my beloved Denon 103R. That is in fact, a big reason I purchased it, since I knew the tonearm compliance is a perfect match for my favourite LOMC (Low Output Moving Coil) phono cartridge. I’ve also always preferred direct drive turntables to belt driven ones. Yes, I know that will open a can of worms that I’ll address in another post (Turntables – Direct Drive vs. Belt Drive), but I will always remain an advocate of direct drive turntables ever since owning one of the finest direct drive turntables ever made, the Techniques SP-10 MkII back in the 1970s. And when searching for a mate for for my Denon 103R matched to the Nelson Pass phono stage found in my Nakamichi CA-5A preamplifier, this was an obvious choice.

I carefully packed it to travel as checked baggage on my flight to Maui (How to pack a vintage turntable) and when I unpacked the box I was pleased that the precautions I had taken resulted in safe passage. Needless to say, high quality audio gear is neigh on impossible to find on Maui. So I imported.

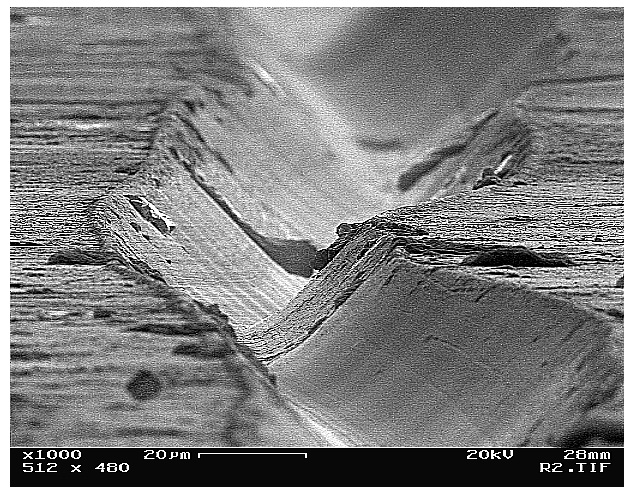

It took me a while to set it all up since it had been years since I had properly set up a turntable. Azimuth, overhang, accurate stylus force, leveling, VTA, cartridge loading, were all tweeted (How to set up your turntable for your phono cartridge). Then, I found this otherwise fantastic turntable’s achilles heel.

Virtually all turntables use one of two methods to deal with acoustic feedback (vibrations from the speakers returning back to the phono cartridge to be re-amplified in a positive feedback loop), either suspension (sprung turntables) or mass loading (Acoustic isolation for turntables – to couple or decouple?…), and this one has neither.

The plinth, while solid, is certainly no example of mass loading, but it also lacks any form of suspension. The only attempt Denon made at acoustic isolation were four grossly inadequate rubber feet. Thus began a quest that lasted weeks – how to isolate this otherwise exemplary turntable.

It was immediately obvious that vibrations from my “equipment rack” (which is an ordinary teak shelving unit that is almost seemingly designed to mechanically amplify vibrations but I like it’s esthetics and know I can do what it takes to modify ordinary furniture to my needs, right?) would be a deal breaker. No problem I thought, just hang the turntable off the wall so that’s exactly what I did and expected good results. Not.

The trouble was the tight bass of my Kef 104/2s was so well coupled to my wood-over-concrete slab floor (coupling is exactly why the bass is so tight) that it transmitted very efficiently and effectively to the wall studs from which my precious turntable was hanging.

What ensued was a methodical study of acoustic isolation techniques. I didn’t really want to re-plinth the deck, it is a frigging perfect example of it’s original glory (or lack thereof in the isolation department). So I experimented with various methods to build an isolation platform for it to sit on. I started with a couple pieces of the hardest and densest wood I could find (they almost feel like granite they are so heavy) then various methods between them in the form of ball bearings (which virtually eliminate horizontal vibration transfer – they now sit under my power amplifier), bicycle inner tubes (don’t over-inflate or it defeats the purpose), Sorbothane feet, spikes (coupling the extra mass to the plinth), and every combination thereof.

What I ended up with is three (in order to offset them from the four feet of the turntable plinth) Vibrapod cones, stacked into three Vibrapods that are rated for the weight of my turntable between the two massive wood platforms, a bicycle inner tube directly under the platter assembly with a straw to let it breathe, along with four Sobrbothane feet under the original feet with reasonably good results.

“Reasonably good?!” I’m sure many of you are asking. Anyone who knows me or reads this blog knows that “reasonably good” is far from good enough. So the quest continues. I plan to further experiment with granite slabs and boxes full of sand (Maui beach sand of course) before I feel I have fully exhausted acoustic isolation techniques. I might still hang the platform from the ceiling but I’m hoping to not resort to such drastic measures. And that’s certainly part of the fun, discovering what works and what doesn’t.

I presently have the acoustic isolation tamed to where it is below maximum listening levels, but barely so. If I “crank it” on some of my fav music that, well… I just love to “crank it” on I’m sort of “dancing with the acoustic feedback devil.” Still… in spite of all my methods. Under the limits test – phono cartridge sitting on non-spinning vinyl, it is unquestionably still there, and rages out of control a mere notch or two above my maximum listening levels. Of course, it’s drastically reduced on spinning vinyl since that presents a “moving target” for the positive feedback loop to occur.

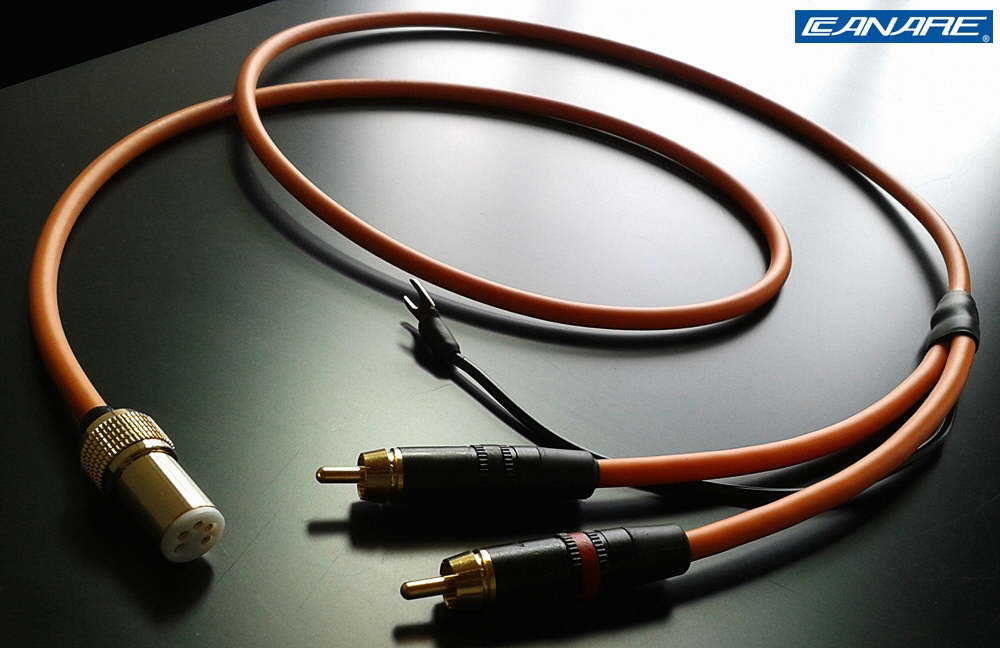

So what started as a turntable review has evolved into a study of acoustic isolation. As for the rest of the turntable attributes?… It is the perfect example of everything I love about direct drive turntables: massive platter, precision speed control (not tied to the frequency of the power outlet as are so many of the lessor belt drive turntables), and virtually non-existent wow and flutter. Also, being that it’s fully manual, the gorgeous tonearm is like a separate component, and shares no circuitry or mechanics with the rest of the turntable. The now upgraded (Time for new tonearm cable?) five pin DIN tonearm cable connects directly to my Nak CA-5A without electrical or mechanical interference of any kind, which is extremely important to me for obvious reasons.

Of course, this means that this remains a fully manual turntable. You cue it up by hand and you get up and pick up the stylus at the end of each side of your vinyl or you are serenaded by that methodical clicking of the stylus on the run-out track. And I wouldn’t have it any other way. If you’re listening to vinyl you’ve already made the choice of superior sound quality over convenience. If you play vinyl with an automatic turntable you might as well fire up your music server and indulge in the full-service (and compromises) that automation offers.

Does anyone else remember the turntables that used to stack multiple records to drop onto the platter in succession?… Just load up a few records and you’ve got a vinyl iPod. That was how it was done back in the 1970s. That is, if not getting out the listening chair was more important than sound quality (and preserving your vinyl).

All-in-all, I couldn’t be happier with this turntable. With Denon’s original direct drive technology, which arguably hasn’t improved since the “golden age” of vinyl, combined with around $100 to $150 spent on my DIY (do it yourself) turntable isolation platform, I have a deck to rivals that of $30k decks today.

Incredulous?… Yes, direct drive turntables, which I’ve been “singing the praises” of for years are coming back in vogue, and selling for $30k. Just have a look at VPI’s (a long time advocate of belt drive turntables), newest addition to their product line, a “classic” direct drive turntable starting at $29,999:

http://www.musicdirect.com/p-157642-vpi-classic-direct-drive-turntable.aspx

Postscript: December, 2014: I’ve used a massive granite slab coupled to the Denon with spiked feet, sitting on a bed of sand in a nice wood box, that sits atop my existing double wood slab isolation platform and have finally accomplished the desired result. Altogether, it weighs in around 150 pounds, which is hung off the wall by two very sturdy brackets. Total cost of the modifications?.. Less than $200. Total cost savings vs. purchasing a modern day equivalent of this turntable?… At least $5k.