You will hear me speak of “reference recordings” a great deal in this blog. These are go-to recordings I use to compare and contrast sound quality when evaluating new gear and/or tweaks I’m making to an existing system, room, speaker placement, etc.

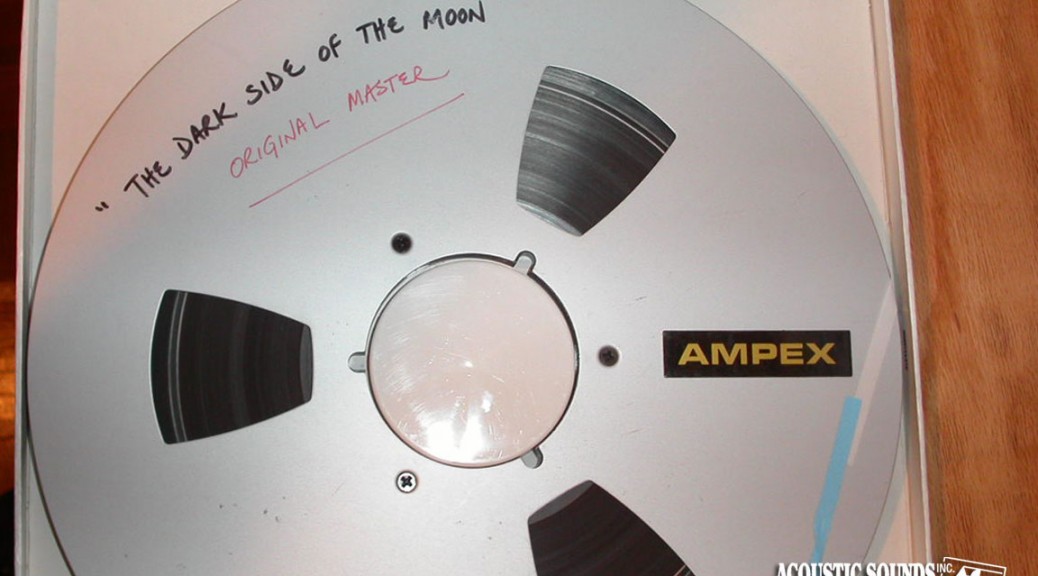

My reference recordings have a few things in common, such as phenomenal dynamic range and a large variety of instruments and nuances of musicality. They are typically recorded by the most fastidious sound engineers in a fashion that provides reproduction as close to the source as possible, though there are also some “happy accidents”. With precious few exceptions, they are fully analog recordings. Which mean’s they are vinyl records (side note – some exceptional recordings were released from the original analogue master tapes directly to reel-to-reel analogue tapes, but these were the exception rather than the rule).

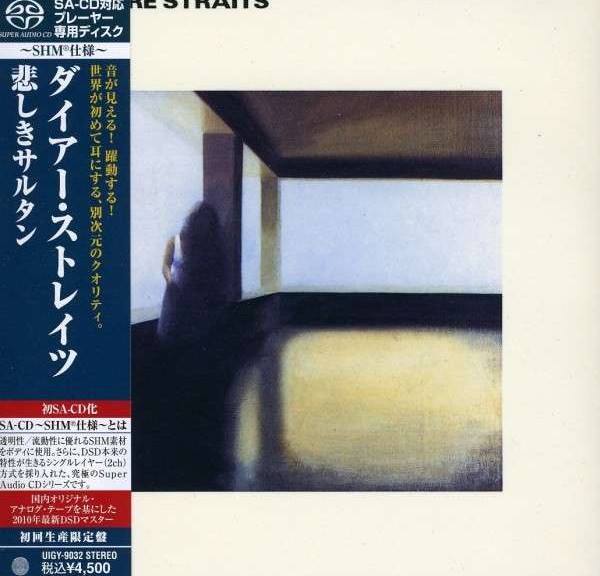

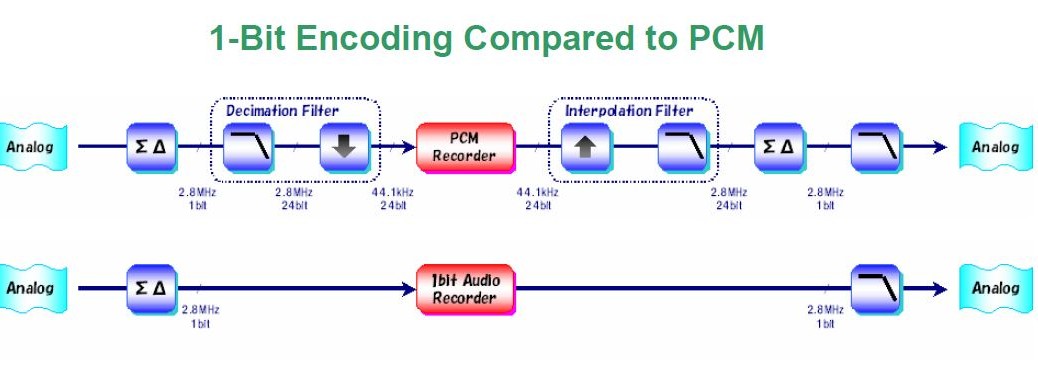

I also have a few digital reference recordings, and they offer the best sound quality I’ve yet heard from the medium, such as: Blade Runner Soundtrack from Vangelis (DSD), Whites Off Earth Now by The Cowboy Junkies (DSD), and a sample track from Blue Coast Recording called “Cali” (Direct to DSD).

The Blue Coast reference is an obvious candidate since they went to great lengths to go from purely acoustic sources in an ideal studio setting captured by some of the best microphones ever made (rare and hand-crafted by Didrik) directly to a native DSD master file. No PCMing or digital mixing. Just the original goods. No more, no less. But this left me wondering why the other two digital recordings were so good…

A little research showed that, due to budget constraints, Whites Off Earth Now was originally recorded directly to analogue master tape in a garage using a single ambisonic microphone. This is far harder for the band to perform, sort of like the Direct to Disc (If one format is better than another, why doesn’t the music always sound better?…) titles offered by Sheffield Labs back in the 70s, This was one of the happy accidents where their low-budget recording method resulted in a raw and visceral quality that would have been lost in an expensive recording studio. And thank goodness they couldn’t afford a professional sound engineer using Pro Tools digital mixing and editing software that would have PCMed all over their original analogue goodness. Then Mobile Fidelity Sound Labs later did their digital magic by carefully transferring the music directly to DSD from these original master tapes (once again, no digital mixing). On a good system that is properly set up, it really does sound like you are there in the garage with the band. Sometimes less is more. This is clearly one of those times.

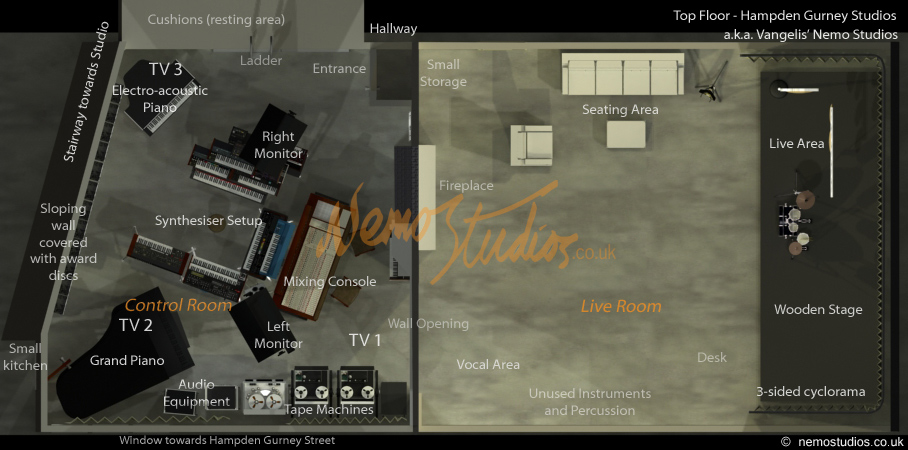

As for the Vangelis Soundtrack, there were many deliberate coincidences. The first was the use of purely analogue tape for the recordings of both the instruments themselves and the synthesizer tracks. “The control room was equipped with two types of tape machines, each dedicated to a certain function in the recording process. The first was a multitrack tape machine capable of recording 24 parallel audio tracks into a 2-inch-wide magnetic tape. The multitrack tape allowed the individual instruments from a performance to be recorded into discrete audio tracks. This gave flexibility during mixing, as each audio element could be treated separately for panning, gain or other fine-tuning. Vangelis’ multitrack tape machine was the Lyrec TR-532, the same tape machine he used to record his solo albums and his film score to Chariots of Fire. The second type of tape machine in Vangelis’ control room was a ‘tape master’ machine that allowed the final mixed work to be produced onto a 2-track quarter-inch master tape.”

And a (thankful) lack of digital manipulation as evidenced by this quote, “While creating music in a multitrack tape studio environment offered immense opportunities for adjusting the recorded performance, it lacked many of the convenient tools that arrived with later technologies, such as mixing desk automation, SMPTE time-code for synchronisation and much of the digital facilities that swept the sound-recording and film production studios in the late 1980s and beyond.” While I view these factors, combined with Audio Fidelity’s (https://audiofidelity.net/about-us) careful transfer directly to DSD, to be the essential reason the quality and nature of this recording survived in the digital age (The “Dark Ages” of High End Audio). there was a great deal more that also went into the perfectionism of Vangelis. More on that can be found here (where excerpt quotes were taken): http://www.nemostudios.co.uk/bladerunner/

Most of my vinyl reference recordings have been “old friends” for decades, but every now and then I drop the needle and find a new one. Most notable recent additions are many of the vinyl releases from Nine Inch Nails (Digital distortion in a purely analog signal path.), David Gilmor’s relatively recent release “Rattle That Lock”, as well as a new discovery of Ben Harper’s “Pleasure and Pain” by Cardas (Pleasure And Pain Ben Harper & Tom Freund).

The point isn’t for me to share my “reference recordings”, though a short list may be a useful starting point if you share my music taste. The point is for you to find your own. That’s the fun part. As you upgrade your system you will start to notice that your music collection will take on new life and sometimes you’ll find a revelatory change that makes you want to listen to your favorite albums all over again. Very soon thereafter you will find you have discovered your own set of reference recordings. Enjoy the journey!